Diamonds Aren't Forever

If you were to ask ten-year old me about the stability of the diamond industry, I’d sing “He went to Jared,” and “every kiss begins with Kay” and guess it was in pretty good shape. And to be fair to myself, until recently, that was the case. But over the last few years, a new player has risen up, threatening the industry’s stability. In so doing, it promises to clean up a bloated industry that is responsible for humanitarian and environmental grief, while also democratizing the financial expression of love.

For the last 2500 years, diamonds have been an object of value, originating in India, before eventually spreading across the world. The modern beginning of these precious stones begins in South Africa, however, when a series of discoveries in the 1860s kicked off a fully-fledged diamond rush. Among the thousands of men who journeyed to the Big Hole at Kimberley, on the Northern Cape, was Cecil Rhodes.

Rhodes, like most of the lucky few who were successful in the diamond rush, was ruthless and well-resourced. After beginning as a lessor of highly sought after water pumping equipment at the site, he used his substantial profits to buy up claims at Kimberley. Over the next two decades, he received outside funding and consolidated the worldwide diamond market into a century-long monopoly under the banner of his company: De Beers.

Between 1888 and the 1980s, it controlled greater than 80% of the world’s diamonds, and it used every bit of its influence to create a cartel that artificially reduced supply. At the same time, it successfully increased demand, launching the famous “Diamonds are Forever” ad campaign, tying diamonds to marriage and exploded its profits. Over the next fifty years, diamonds went from a rarity in the marriage space to a necessity, and De Beers was able to hike its prices exorbitantly on the back of its monopoly. Don’t just take my word for it; Milton Friedman himself described the diamond monopoly as one of only two that had existed over a long time without government assistance.

Predictably, the rising popularity of diamonds required more mining, subjecting workers to dangerous working conditions, diseases, death, and is tied to child labor, human trafficking, human rights violations, torture, and environmental catastrophe. It is also built upon an exploitative system in which the lowest workers earn a pittance, but have no other options for employment. In Sierra Leone, for example, one can make as little as 15 cents a day. I’m currently reading The Jungle, and even in 1905, the 12 year old Stanislovas made more than that.

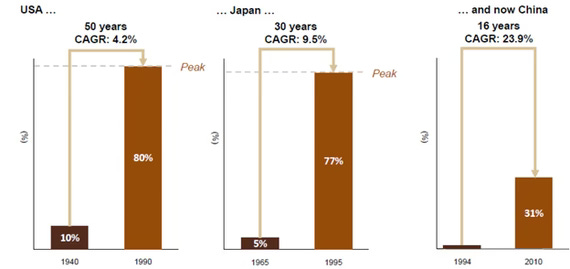

All this brings me to the lab grown diamond. Scientists created the first lab grown diamonds in 1954, but it took another 17 years for the first “gem-quality” diamonds to be made, and further iterating to perfect the product. In 2018, the FTC ruled that they were akin to diamonds. Consumers, who increasingly focused on ethics and sustainability in their purchases, were searching for an alternative to the much maligned natural diamond. Ironically, De Beers played its own role in this market shift, pushing lab grown diamonds in an effort to create a two-tiered system that highlighted the superiority of the natural product. This backfired, and while analyses of the diamond market are variable, all agree that lab grown diamonds have rapidly increased their share of the diamond market in the last five to seven years.

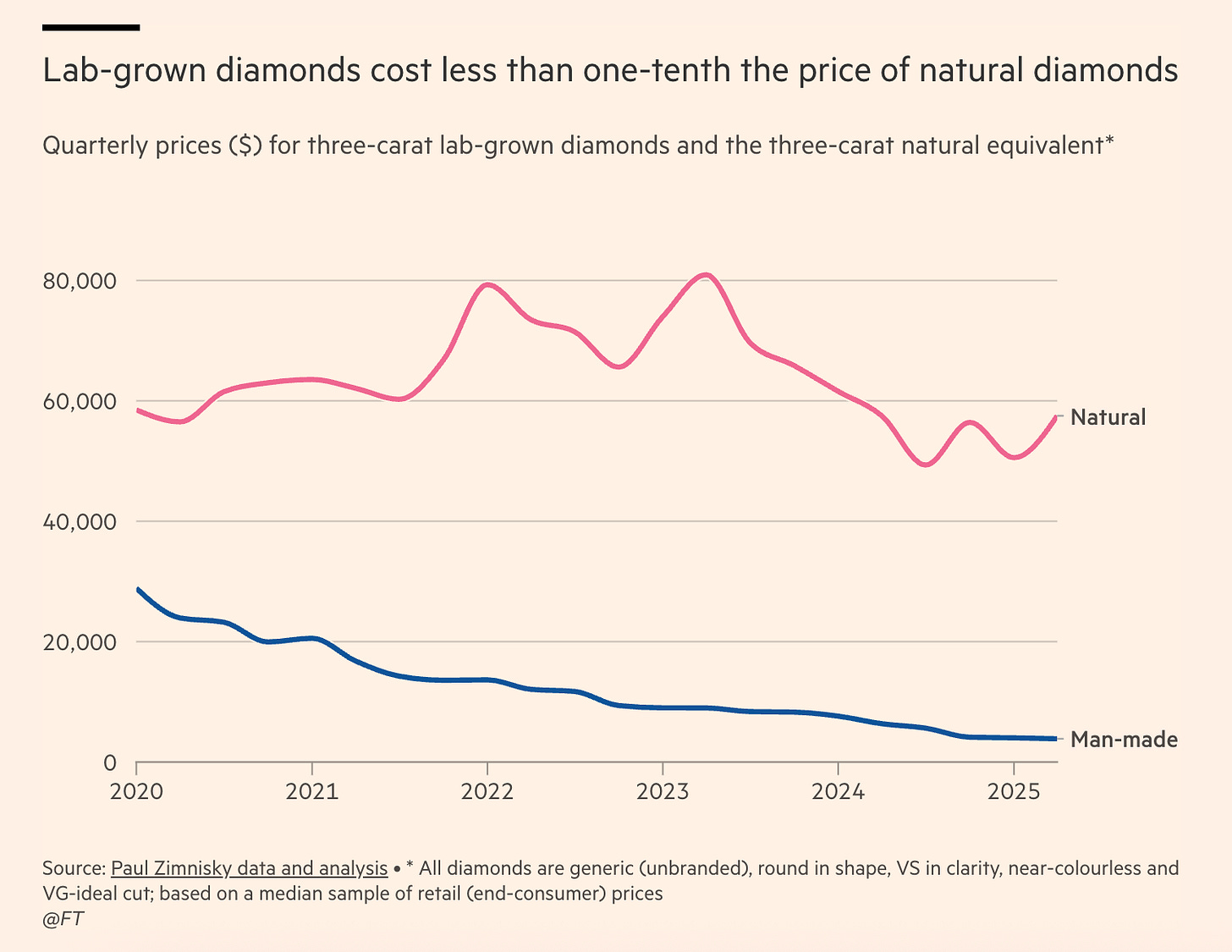

It’s not difficult to see why. Lab grown diamonds equal natural ones in quality, while also costing a fraction of the price. As lab grown manufacturing has scaled, consumers have also reaped the rewards; in five years, the cost of lab grown diamonds has plummeted, from ~$30,000 to ~$5,000 for a similar quality diamond. In contrast, as previously mentioned, natural diamonds are a product of artificial scarcity.

In addition, lab grown diamonds emit a fraction of the emissions as natural ones, with some estimates suggesting that natural diamonds result in 6,000 times as much mineral waste as lab grown. Lab grown diamonds also don’t come with the risk of disaster, lung disease, or death that is common in the mining community, satisfying at least some of the ethical concerns that natural diamonds fall short on.

These advantages have devastated the natural diamond market. De Beers’ market share had already crept down from the near monopoly in its heyday, but it has experienced grave losses in the last couple of years as demand has shifted. The same is true for Alrosa, the big Russian diamond producer. Rarely do disruptions to a market happen with such velocity as the diamond one, but the lab grown boom is an exception.

The decline of the natural diamond market is cause for celebration. As H.R. Haggard writes in the 1896 classic book King Solomon’s Mines:

“Truly wealth, which men spend all their lives in acquiring, is a valueless thing at the last.”

Men spend their lives in the mines, risking their lives and long-term health for a pittance, because it is their only option. There are many outstanding questions: will lab grown diamonds lose steam; will natural diamond prices fall; will the pendulum shift, as consumers find lab grown diamonds too cheap to be a symbol of matrimony?

The future is uncertain, but this change is surely exciting. At the very least, it offers choice for newlyweds to be; at best, it threatens an industry that must make massive changes to exist in a world we hold to a higher standard. And it adds a little more mystery to the whole enterprise; the next time you see a ring on a newly engaged person’s finger, try to tell whether it’s natural or lab-grown. I bet you can’t.

This piece feels inspired 👀

Do you want to tell me something?