A few days ago, Jimmy Carter passed away at the age of the 100. He was our greatest humanitarian president, one of the few whose time in office was substantially overshadowed by his post-presidential life. He was a Nobel Peace Prize winner for his efforts to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, for decades he volunteered for Habitat for Humanity, and he was crucial in creating the American home brew industry. There are countless reasons to pay homage to our longest-lived president—a profoundly good man—but perhaps his greatest and most underrated feat is his immense role in the near-eradication of guinea worm.

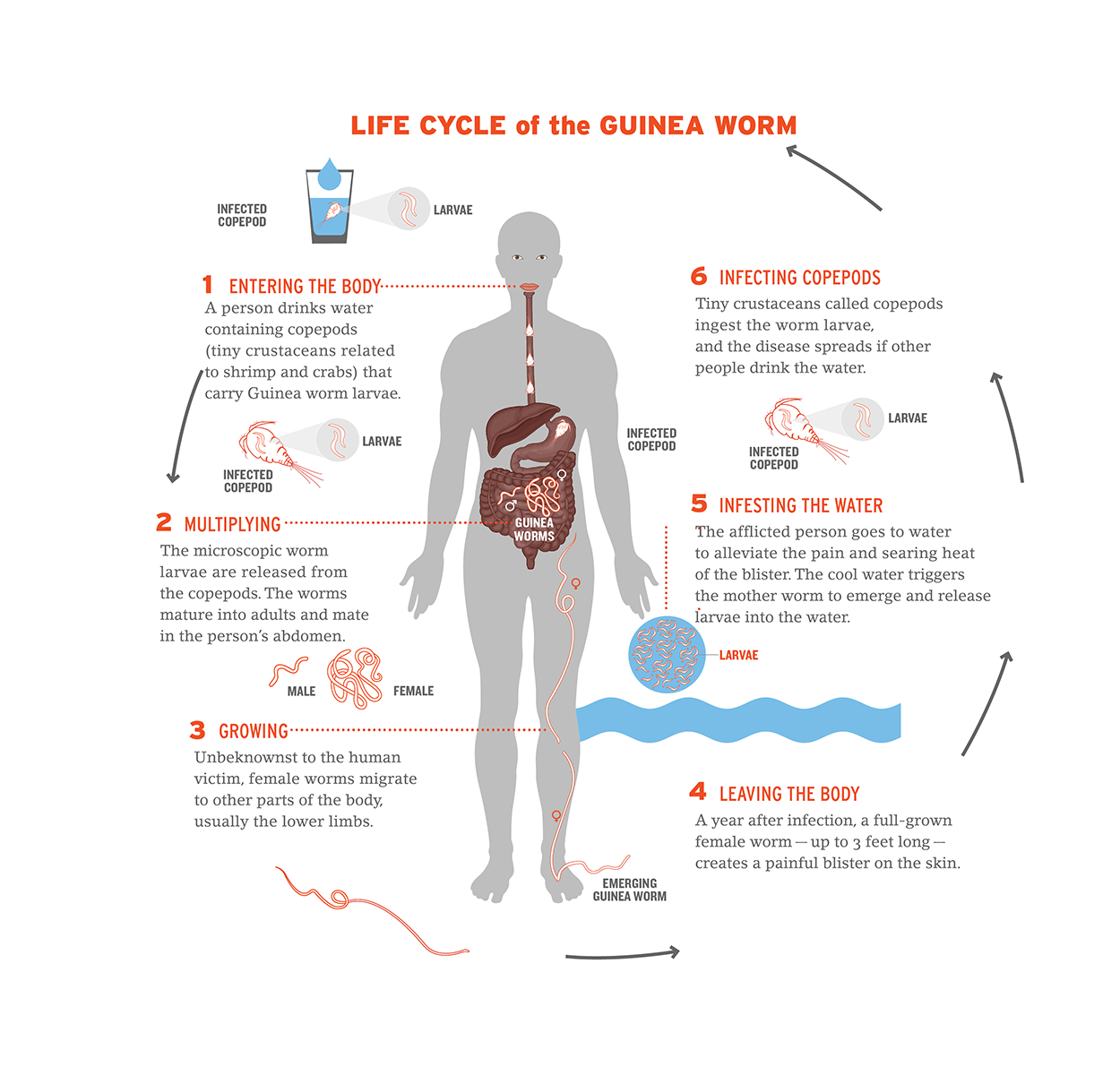

Guinea worm is a parasitic disease usually caused by the drinking of contaminated water. The disease is rarely fatal, but a year after contamination, symptoms, which include blisters, burning, and pain, become present as a worm begins to emerge from a person’s skin, typically from the foot. This can result in infection, limited mobility for several weeks, other wound complications like tetanus, and pain that lasts for months on end in some cases.

In addition, a common pain management strategy spreads the disease. As the worm emerges, people occasionally place the infected area in water to lessen the burning sensation. This leads to the worm releasing larvae into the water, contaminating that water source, and ensuring that anyone who drinks from it might contract the disease. A single worm can cause 80 or more cases the following year, allowing guinea worm to spread exponentially.

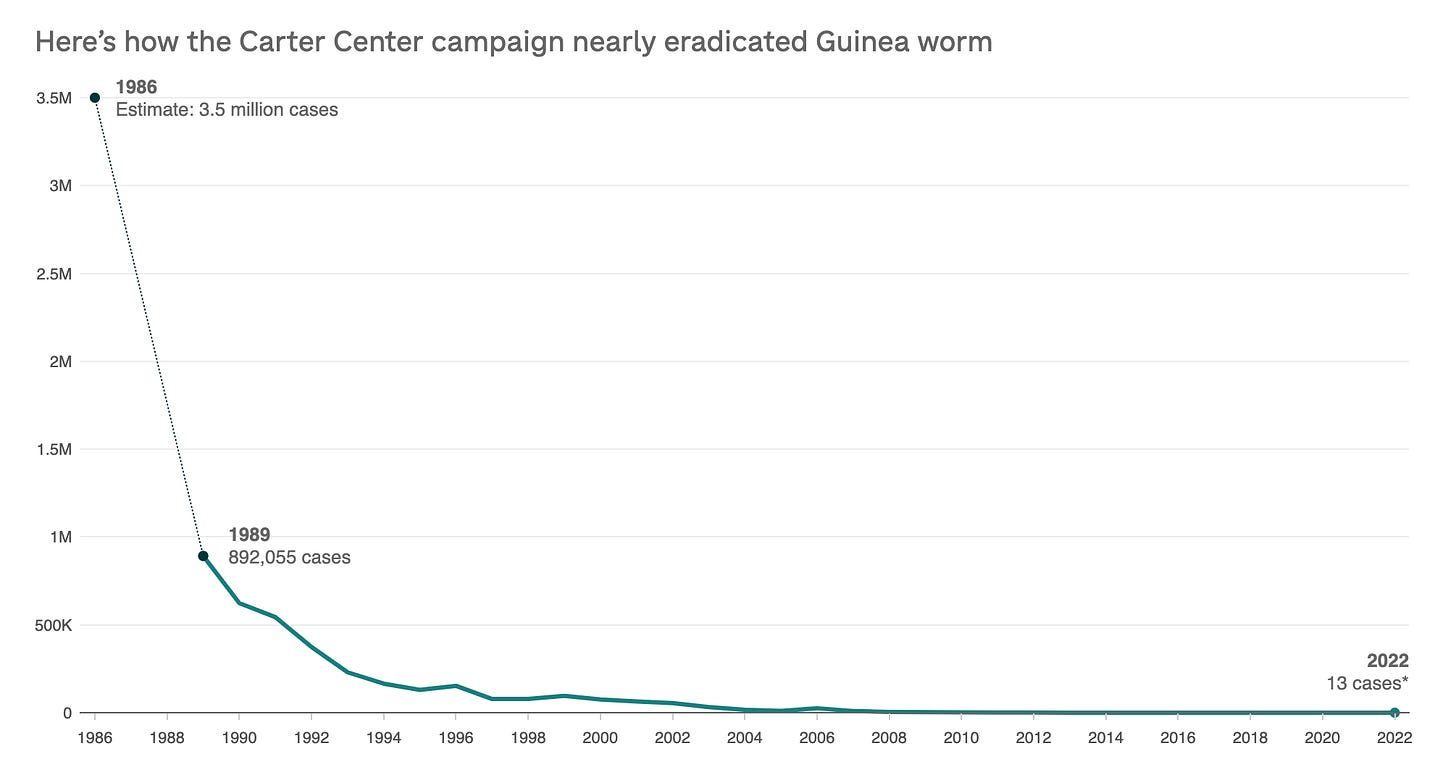

During the mid-1980s, guinea worm afflicted 3.5 million people in 20 countries. It was at this time that the international community began to call for solutions. In 1980, the CDC announced its intention to eradicate guinea worm, and the elimination of the disease was included as part of the goals of the United Nations’ First Water Decade. It was determined that guinea worm was preventable by public health measures—particularly increasing access to clean water and educating the public about the disease and warning afflicted persons of the ramifications of placing the infected area in drinkable water.

Unfortunately, for all the talk of the need to fight this affliction, guinea worm was not prioritized for several years. In 1986, that changed, when Jimmy Carter, then several years removed from his presidency, decided to involve himself. It was one of several under-discussed diseases caused by drinking water that caught Carter’s eye and the Carter Center, founded in 1982, took up the leading role in the campaign to end guinea worm, partnering with local health ministries, as well as international organizations like WHO and the CDC.

In 1987, Pakistan and Ghana became the first countries to receive assistance from the Carter Center. In 1988, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter traveled to Ghana, and witnessed firsthand the devastating effects the disease had upon villagers there.

Over the last thirty-seven years, the Carter Center has taken a multipronged approach to ending this pestilence. Millions of water filters have been deployed to protect from contaminated water. Prevention efforts were undertaken to keep anyone with an emerging worm from entering a water source. A premium has been placed upon early detection, with suspected patients encouraged to seek assistance and cash rewards implemented for those who successfully report suspected cases.

The Carter Center has also trained one hundred thousand community-based health workers, and thousands of volunteers have been deployed to help educate the public on the threat and the appropriate steps for prevention and containment. And to do all this, the Carter Center has invested $500 million since 1986.

And at times, Carter used his other talents to fight the disease. In 1995, Carter negotiated the longest humanitarian ceasefire in history, leading to a six-month pause in the Second Sudanese Civil War. This allowed aid workers to enter previously off-limits places and help counteract the disease; at that point there were three times as many cases in Sudan as the rest of the world combined.

The results of the Guinea Worm eradication campaign have been nothing short of extraordinary. By 1989, three years after the Carter Center became involved, cases dropped nearly 75%. Pakistan and Kenya became the first within the eradication program to stop the disease in 1993 and 1994, respectively, and by that point there were fewer than 500,000 cases of guinea worm.

As the years passed, the Carter Center, aided by humanitarian organizations and cooperative governments, continued to tackle the problem. In 2001, the Carter Center sent 9 million pipe filters to Sudan—enough for every person at risk for the disease—to prevent the consumption of contaminated water. In 2003, Ghana’s government employed thousands of Red Cross workers to assist with eradication, and in 2010, the country stopped transmission.

In 2024, there were 11 confirmed human cases of guinea worm in the entire world, a slight drop from 14 in 2023. Over less than forty years, guinea worm cases have fallen by 99.9996%. 6 countries remain guinea worm endemic, down from the 20 in the mid 1980s. This is a monumental achievement that places guinea worm closer than any other disease to becoming the 3rd infectious disease eradicated, after smallpox and rinderpest.

The road to eradication, from 11 cases to 0, is not without obstacles. To fully end a disease, to find every last case, requires heightened surveillance. Conflict in South Sudan, Central African Republic, and Mali may hinder efforts to provide assistance and volunteers to areas that need it. And in Chad, guinea worm has been slowly increasing not among humans, but dogs. There remain fewer than 1,000 reported cases in animals in 2023, but as we stand on the very precipice of ending the disease, its transmission to a new species is cause for concern.

Nevertheless, the past forty years have been a story of triumph. It would be foolish and dismissive to ascribe all credit to Carter; this was a global collaboration between governments, non-profits, health workers, and ordinary people who all came together to vanquish this pestilence. Yet, it is apparent that Carter was a driving force in tackling this disease, utilizing his diplomatic ingenuity, his passion for addressing lesser known maladies, and the vast resources at his disposal to enact real change.

It was President Carter’s goal for the last guinea worm to die before him. While it does not appear that he fully reached that lofty mark, the near eradication of guinea worm in less than four decades is one of his—and public health’s—greatest accomplishments.

And it suggests that if another person of Jimmy Carter’s caliber and resources, rare though that person may be, decides to set their mind to a task just as ambitious as the eradication of guinea worm, there is no telling what they can accomplish.

Jimmy Carter dies and RFK Jr. ascends. Thank you for the note of hope, Caleb Apple. It will take some work for us to support the former's legacy and shut down the latter. 2025, here we go.