A Reduction in Crime

If you read or watch local news, there’s a good chance many of the top stories are about crime. Crime is an omnipresent topic of discussion, from people asking their friends if they heard about a robbery down the street, to politicians levying various claims about the levels of crime in their communities. Based on how personal, scary, and oft-discussed crime is, it’s unsurprising that 77% of Americans believe crime is on the rise. But while it’s true that violent crime spiked during and just after the pandemic, the last couple years have reversed that trend, an encouraging sign after decades of progress on crime reduction in America.

New York City is in many ways emblematic of America’s crime trajectory. In the 1950s and 1960s, white flight set the stage for a gradual deterioration of fortunes in the city, with lack of investment and funding leading to a city fiscal crisis which yielded the famous headline: Ford to City: Drop Dead. Crime rates rose precipitously until 1970, and then continued to a record high of 2,245 homicides in 1990.

In the 1990s, the homicide rate fell rapidly, and by 2000 there was 673 homicides in the city, a reduction of roughly 70%. By 2019, there were 319. Oft lambasted for its crime rate, New York is now one of the safest big cities in America.

This trend is broadly similar to other cities across the country, with certain differences in context. In DC, crime doubled between 1972 and 1991 to a peak of 509. In 2012, it hit a record low of 88 homicides, before unfortunately rising upward to 166 in 2019. In Chicago, homicides fell until 2016, a year of particular tragedy in the city, and then declined again until the pandemic. In Los Angeles, crime was reduced fourfold between 1990 and 2010. In St. Louis, the city with the highest violent crime rate in the US, violent crime halved from 1990 to 2019.

There are a number of theories about what caused this rapid decrease: increases in median income; the use of data programs like New York’s CompStat; improvements in environmental factors like the reduction of lead pollution in drinking water; increases in the chance that criminals will be caught.1 Measuring the precise impact of each of these different policies is difficult, but it’s clear that a number of factors have played a role in substantially reducing crime rates.

It is also undoubtedly true that high violent crime rates gave credence to policies of mass incarceration, particularly of Black and brown men, that have disempowered communities and continue to this day. However, there appears to be little evidence that these policies played a role in the reduction of crime; in fact, research suggests that lengthy sentences and harsher punishments are not only an ineffective deterrent, but can also increase recidivism rates. While the US has made some progress, reducing the prison population by 24% in the last decade and a half—including 46% among Black Americans—it remains woefully insufficient.

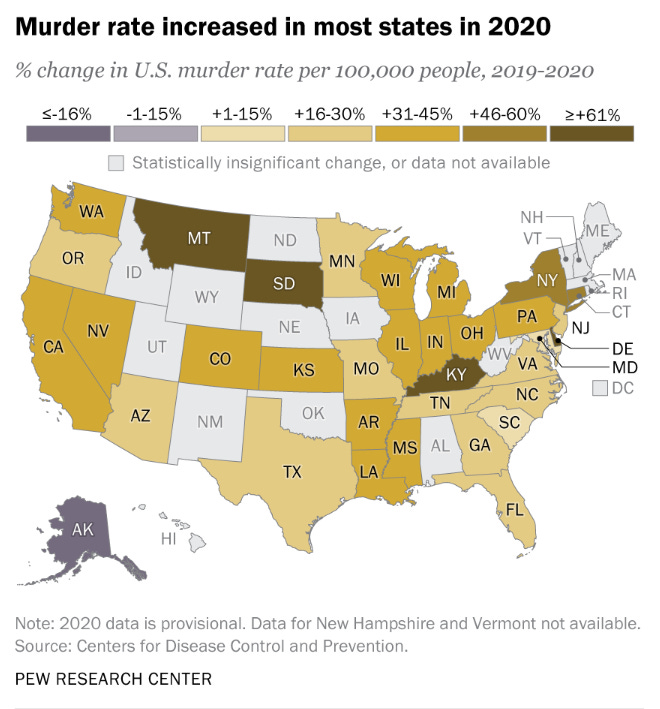

The pandemic threatened to undo decades of progress on crime reduction, as it did on so many other areas as well. During the pandemic, homicides rose by 30% year over year, the largest jump in crime in a century. This was a nationwide jump, although the highest increases came in Montana, South Dakota, Delaware, and Kentucky. Like with the drop in crime, the reasons why crime rose are hotly debated, from a general increase in antisocial behavior during the pandemic, to worsening relations between police and communities, to record gun sales in 2020. As well, root causes of crime like poverty and cost of living were exacerbated during the pandemic.

While violent crime remained far below the nadir of the 1980’s and 1990’s, this increase was obviously of grave concern and policymakers, criminologists, police officers, and all Americans had good reason to wonder whether the pandemic was a temporary blip, or a new normal. Four years onward, we’re closer to answering that question, with the evidence thankfully pointing far more toward the latter.

In 2021, homicides declined by 4.7%, before rising by 1.5% in 2022. Then, from 2022 to 2023, homicides dropped off a cliff, declining by 11.6% nationwide. The rate of decline only seems to be accelerating in 2024. Jeff Asher, a crime data analyst, has compiled real time crime data for 277 cities, including the largest in the US, and estimates that murders are down 18% in 2024 YTD.

New York City is a useful example once more. In 2019, as previously mentioned, there were 319 homicides. In 2020 and 2021, this number rose to 468 and 488 respectively, before falling to 438 and 391 in 2022 and 2023. This year, New York City is on pace for 345 homicides. In other cities, the crime reduction has been even larger. Detroit, a city often tarnished as an epitome of urban decline, has continued its trend of revitalization, wracking up its fewest homicides since 1966 in 2023. So far in 2024, homicides have decreased by 19%. In New Orleans, which recorded the highest murder rate in the country in 2022, homicide rates dropped by 27% in 2023, and are on pace to drop a further 41% in 2024. Put another way: there were 266 homicides in 2022, and this year New Orleans is on pace for 115.

Boston, a longtime success story for its Boston Miracle, a policing intervention strategy implemented in the 1990’s to tackle youth gun violence, has had 16 murders in 2024, down from 30 in the same period last year, staking its own claim for the safest American big city.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t exceptions. DC, for example, hit its highest number of homicides in 2023 in 20 years. It has been beset with several problems in recent years, including its crime lab losing accreditation, an increase in illegal guns in the District, and a prosecution rate substantially lower than peer cities. Yet, data from 2024 suggests that violent crime in DC is also trending downwards, likely aided by the re-accreditation of the crime lab, an increase in prosecution rates, and further distance from the pandemic.

These past few years have also yielded a number of attempts to address mass incarceration, both by reducing it going forward and minimizing its impact on those already impacted. Most Americans now live in a state where weed is legal, a significant step forward after decades of the War on Drugs, and Vice President Harris’ platform supports legalization nationwide. Several states have also passed laws in recent years to restore voting rights to citizens on parole, and twelve states have adopted Clean Slate laws, which automatically seal records for certain criminal convictions, allowing formerly incarcerated people to have better access to jobs and housing.

The U.S. still has enormous work to do to reduce homicides. Tens of thousands of people are murdered every year, and the US has a homicide rate significantly greater than most other developed countries, driven principally by ubiquitous guns and poor gun regulation. At the same time, policymakers must be obliged not to simply default to mass incarceration as an illiberal, ineffective tool to reduce violent crime. The past couple of years are a positive sign, suggesting that we can both continue a three-decade trend of violent crime reduction while also reducing and reversing the legacy of mass incarceration, ensuring a future that is both safer and more equitable.

This is different than increasing how harsh punishments are